BIBLE STUDIES

Downloadable · Shareable · Created by Yale University women

Mother, May I?: Learning from Biblical Mothers (2025) by Anna Grace Glaize

Christmas According to Luke (2024) by Anna Grace Glaize

Women in the Bible: The Overlooked & Misunderstood, A Four-Week Study (2024) by Anna Grace Glaize

Holy Week Wonderings: Women of Holy Week Study (2024) by Anna Grace Glaize

The Women Who Made Jesus: a Four-Part Advent Study (2023) by Anna Grace Glaize

FEATURED STUDY:

THE WOMEN WHO MADE JESUS: A Four-Part Advent Study

By: Anna Grace Glaize

Tamar begat Perez and Zerah of Judah

Rahab begat Boaz of Salmon

Ruth begat Obed of Boaz

Obed begat Jesse

Jesse begat David

Bathsheba begat Solomon of David

This four-part Advent study explores the stories of the foremothers of Jesus. While it’s intended to be used during the liturgical season of Advent, there’s no reason it can’t be used at any other time of the year if you’re interested in learning about the women in Jesus’ genealogy. You’re welcome to use it as an individual resource or in a group setting. Background information and resources for further reading are provided, discussion questions are embedded throughout, and each section ends with a short prayer.

We hope you find this study useful, and we pray you’ll be blessed by your journey with Jesus’ female ancestors. May you find strength in these women, and may you have a joyful Advent.

INTRODUCTION

Read Matthew 1:1-17

The Gospel of Matthew begins with the genealogy of Jesus, linking Jesus to the patriarch Abraham and King David. In Matthew’s genealogy, five women are included — Tamar, Rahab, Ruth, the wife of Uriah (Bathsheba), and Mary. That any women are present is surprising given that women weren’t usually included in genealogical lists. These genealogies were quite literally patriarchal. Even more surprising is which women the author of Matthew chose to include. The four women listed from the Hebrew Scriptures/Christian Old Testament bring to mind “aspects of Israel’s past that some might think should best be forgotten.” (1)

So why does Matthew choose to include these women? And what does the inclusion of these women say about Jesus? Biblical scholars agree that these women have at least two things in common which might direct us toward the answers.

Firstly, all of these women illustrate the Jewish Jesus’ Gentile ancestry. Tamar lived in Abdullam and was probably a Canaanite. Rahab was a Canaanite prostitute living in Jericho. Ruth was a Moabite. Bathsheba was married to Uriah the Hittite and is identified as “the Wife of Uriah” in Matthew’s genealogy (Matt 1:6). Matthew includes these women to remind his audience that non-Israelites played a role in the ancestry of King David, King Solomon, and now Jesus. Their inclusion in the genealogy foreshadows Jesus’ ministry to Gentiles.

Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, each woman’s story includes some degree of scandalous sexual activity. These women are not condemned for their actions within the biblical text. Instead, each woman’s story includes the conception of some of Israel’s greatest leaders. By invoking these women, Matthew prepares his audience for a truly shocking conception story—the conception of Jesus by Mary through the power of the Holy Spirit.

As we begin our journey with the foremothers of Jesus, we’ll embark with this important reminder: we are called “to look for God at work in unanticipated and scandalous ways.” (2)

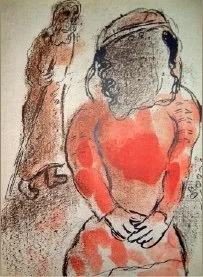

PART 1: Tamar

“Tamar Daughter-in-Law of Judah” by Marc Chagall, from Bible Odyssey.

Read Genesis 38.

Tamar’s story appears in Genesis. It comes immediately after the patriarch Jacob’s son Joseph is sold into slavery. You might have heard about the remarkable robe Jacob had made for Joseph, and how his other sons were very jealous of their little brother Joseph. They threw Joseph into a pit where he was found by slave traders, sold into slavery, and eventually became an advisor to the Pharaoh. Tamar’s story interrupts the story of Joseph. When her story takes place, neither Joseph’s father nor his brothers know what’s happened to Joseph.

Judah was one of Joseph’s brothers and Tamar’s father-in-law. After Tamar’s husband Er dies, she’s given in levirate marriage to Judah’s other son, Onan. Levirate marriage was used to solve the problem of a man who died childless and what to do with the wife he left behind. A widow would marry the brother of her deceased husband, and any child produced by the union would be seen as the child of the dead man. (3)

Onan knows that any child he has with Tamar will be considered Er’s, and that child would inherit property that could otherwise go to Onan. So Onan purposefully does not impregnate Tamar. This angers the LORD, and Onan dies. At this point, Judah thinks something must be wrong with Tamar. He sends her away to her father’s house and does not marry her to his youngest son, but he also doesn’t release her to marry someone else. She’s trapped in perpetual widowhood, childless, which was a very precarious position.

When her father-in-law goes to a sheep-shearing festival, Tamar takes off the clothes that mark her as a widow and dons a veil. She goes to a crossroads between Enaim and Timnah. On his way back from the festival, Judah sees Tamar, assumes she’s a prostitute, has sex with her, and, unbeknownst to him, performs the levirate by impregnating Tamar. Before Judah leaves, still unaware of Tamar’s identity, he gives Tamar his signet and cord.

After Judah finds out Tamar is pregnant, he orders she be burned, even though stoning was the traditional punishment for adultery. But Tamar produces the signet and cord, and Judah is forced to admit his own wrongdoing, saying, “She is more in the right than I, since I did not give her to my son Shelah.” Tamar gives birth to twins, an auspicious sign in the ancient world, and she names them Perez and Zerah.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS:

Clothing and personal items play an important role in Tamar’s life. Once she changes her clothes, her life starts to change. By taking Judah’s signet and cord, Tamar has the tools to save her own life. Do women today still use clothes to negotiate their way in the world? How so?

Interestingly, the text never says whether Tamar intended to be perceived as a prostitute. It only says Judah assumed she was one. What assumptions do we make about people based on how they’re dressed?

In Genesis 38:11, Tamar’s life comes to a standstill by being ordered to go back to her father’s house, childless and unable to remarry. She then goes to a literal crossroads in Genesis 38:14. When have you felt stuck? What got you unstuck? What have been the major crossroads in your life?

Scholar Tikva Frymer-Kensky says Judah’s role in Tamar’s story shows that “a man with both power and lack of understanding becomes an oppressor.” (4) Has there ever been a time in your life when harm was done to you because of a lack of understanding? Or when you caused harm? When have you witnessed a lack of understanding cause harm in the world?

What do you think Jesus may have learned from his ancestor Tamar? What have you learned?

Closing Prayer: God of the Crossroads, help us learn from Tamar. Help us discern when we are stuck, and give us strength to choose change. May the changes we make in our lives lead to more compassion and greater understanding. Amen.

PART 2: Rahab

“Rahab and the Emissaries of Joshua,” Italian School, 17th Century, from Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of the Vanderbilt Divinity Library.

Rahab appears in the Book of Joshua. Joseph, after being sold into slavery in Egypt, became a great leader to the Egyptians. His family came to Egypt during a famine and received grain. The Israelites thrived there, until a king who did not know Joseph ruled over Egypt. He enslaved the Israelites and treated them harshly until God freed them. After the Israelites escaped slavery in Egypt, they wandered in the wilderness for forty years. When their leader Moses died, Joshua led the Israelites. Joshua brought the Israelites into the promised land, the land given to their ancestor Abraham, only to find the land already occupied by the Canaanites. The Book of Joshua tells the story of how the Israelites conquered Canaan.

Read Joshua 2.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS:

What does the Bible say about Rahab’s occupation? Does it say anything negative about her work as a prostitute?

Besides her occupation, what do we learn about Rahab from Joshua 2?

Read Joshua 6.

Many readers throughout history have been troubled by the destruction of the Canaanites. It’s important to know the concept of “herem” (often translated as “devoted to destruction” or “utterly destroy”) is at work in the Book of Joshua. “Herem” is most often used in the context of war, with the deity as a divine warrior. The word “herem” appears in other Semitic languages, and the concept of holy warfare was likely widespread in the Ancient Near East. (5)

Moreover, the Book of Joshua is not a history book, or at least not a history book in the modern-day sense of the word. The authors of Joshua wrote a story centered “around a theological perspective rather than a chronological account.”(6) While there are indeed giant crumbled brick ruins in Jericho, archaeologists have dated them to before the time of the conquest of Canaan. (7) It’s likely the authors of Joshua saw or heard about these ruins and wove them into the legends and stories of their people. They’d heard Joshua helped conquer Canaan, knew the ancient city of Jericho was in Canaan, and knew Jericho was home to some impressive ruins, and thus the legend of the walls crumbling down was born. The best legends are often stories that have been embellished.

Even as we read Joshua from a theological perspective rather than a historical one, “... as modern readers and interpreters, we cannot use the book of Joshua as a justification for war and genocide. Even if we appreciate the theological nuances of this biblical text, we should continue to be troubled by its grimly violent understanding of God’s work in history.” (8)

It’s also worth noting that the destruction of Jericho seems to run counter to God’s promise to Abraham that his descendants (the Israelites) will be a blessing to “all the families of the earth” (Genesis 12:1-3). Rahab’s presence provides a sense of irony to the story, as well. “Rahab, who begins as triply marginalized - Canaanite, woman, prostitute – moves to the center as bearer of a divine message and herald of Israel in its new land.” (9)

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS:

What does it say about God that God chose a Canaanite prostitute to be a hero in Israel?

Rahab is a surprising hero in the Book of Joshua. Who are the surprising heroes in your life?

What do you think Jesus learned from Rahab’s story? What have you learned?

Closing Prayer: God of Surprises, may we listen to the voices from the margins. Help us remember that amongst our enemies may be a Rahab, waiting to tell us your truth, reminding us we’re called to be blessings. Amen.

PART 3: Ruth

“Naomi entreating Ruth and Orpah to return to the land of Moab,” by William Blake, from Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of Vanderbilt Divinity Library.

Read The Book of Ruth. (If you’re short on time and in a group setting, you can break up into four groups, with each group reading one chapter. Then, have each group summarize what they’ve read so everyone gets the full story.)

The Book of Ruth is one of two books in the Protestant Bible named after a woman. Though named after Ruth, it’s as much Naomi’s story as Ruth’s. After all, it’s Naomi who’s caught in a near-impossible situation, and it’s Naomi who undergoes the most drastic character change. While Boaz ends up as Ruth’s husband, the Book of Ruth isn’t really about their love story. The love story at the heart of the book is between Ruth and Naomi. It includes some of the most beautiful lines in the Bible: “Where you go, I will go; where you lodge, I will lodge; your people shall be my people and your God my God. Where you die, I will die, and there will I be buried. May the Lord do thus to me, and more as well, if even death parts me from you!” (Ruth 1:16-17).

Ruth the Moabite displays incredible loyalty to Naomi, and this loyalty is what saves both women as they navigate their way through a precarious situation. Recall Tamar and the practice of levirate marriage, which was a solution for widows with no sons to take care of them. Naomi tells Orpah and Ruth she has no sons for them to marry. There is no solution to their predicament other than return to their Moabite families. Israelite society operated within patriarchal family structures, and childless widows had to depend on the kindness of their communities. That’s why there are so many instructions to care for widows throughout the Bible—widows were incredibly vulnerable. Ruth’s devotion to Naomi is not just touching, it’s radical; Ruth“commits herself to an old woman in a world where life depends upon men.” (10)

Ruth meets Boaz through gleaning, the practice of gathering what’s leftover from a harvest (Deuteronomy 24:19). When she tells Naomi, Naomi recognizes Boaz as a relative. Naomi concocts a daring plan that involves Ruth putting herself in a somewhat dangerous situation. Naomi tells Ruth to go to Boaz at night when he’s in the threshing room. The threshing room would not have been very private. Ruth risked, at the very least, damage to her reputation. But Ruth goes anyway and follows Naomi’s instructions up to a point. Rather than following Naomi’s advice to let Boaz tell her what to do, Ruth tells him what to do: “Spread your cloak over your servant, for you are next-of-kin” (Ruth 3:9). This Moabite widow instructs an Israelite man to take up the responsibility of a kinsman-redeemer. (11)

Though another man technically has more right to the role, Boaz gets approval to act as Naomi’s next-of-kin. He marries Ruth, and they have a son. The women of the town name the child Obed, and they tell Naomi, “He shall be to you a restorer of life and a nourisher of your old age, for your daughter-in-law who loves you, who is more to you than seven sons, has borne him” (Ruth 4:15).

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS:

Ruth and Naomi are not related by blood but are bound together by love and shared experience. Are there people in your life who you’re not related to but consider family?

Ruth is incredibly loyal to Naomi, but she’s not always obedient. She stays with Naomi even after she’s told to go back to her family, and Ruth doesn’t do exactly as Naomi instructs when she approaches Boaz on the threshing room floor. Have there been times in your life when you’ve gone against the advice of someone you loved? How do you discern when to listen to loved ones and when to do what you think is best?

At the beginning of the story, Naomi is so overcome with despair that she seems to overlook Ruth’s loving presence. Have you ever been in such a situation? How does Ruth care for Naomi in her despair? When you’re physically, mentally, or spiritually unwell, how would you like to be cared for?

Naomi goes to Moab because of famine. Ruth leaves Moab with Naomi because of devastating personal loss. At different points in the story, both women leave what is familiar to them. Have you ever left what’s familiar to you? What prompted that decision? What new opportunities did leaving provide?

What do you think Jesus learned from Ruth’s story? What have you learned?

Closing Prayer: God of the Widow and the Foreigner, thank you for the families we’re given and the families we make. May we learn from Naomi, who lived through despair, and may we learn from Ruth, who would not leave her side. Amen.

PART 4: Bathsheba

“David's Promise to Bathsheba” by Gerbrand van den Eeckhout, circa 1642, from The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Read 2 Samuel 11.

In both sermons and popular culture, Bathsheba is often portrayed as a seductress. Recently, many women readers have noted the cruelty of this portrayal. (12) King David first sees Bathsheba when she’s bathing. That she’s on a roof is not proof of exhibitionism. Her bath was likely either a ritual bath after her menstrual period or a hygienic bath. That King David sees her “is attributed to the size and position of the royal residence and not to any temptation or solicitation on her part.” (13) There’s also the damning detail that David is in the city at all. It’s springtime, “the time when kings go out to battle,” and all of Israel is at war (2 Samuel 11:1). Yet David is in Jerusalem.

King David summons Bathsheba and has sex with her. This encounter can hardly be considered consensual as he’s the king, her husband is away, and messengers are sent to her house to retrieve her. Bathsheba is impregnated by David and suddenly David is forced to face the consequences of his actions. The text goes out of its way to demonstrate that Uriah the Hittite is a more righteous man than the great Israelite king. Bathsheba is married to a brave and righteous man, and David, out of fear of discovery not love for Bathsheba, ensures Uriah is killed in battle. Bathsheba mourns her husband and then marries the man who had her husband killed.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS:

Leonard Cohen’s song “Hallelujah” references the David and Bathsheba story, using lines like “You saw her bathing on the roof/Her beauty and the moonlight overthrew you.” What are the consequences of blaming a woman’s desirability rather than a man’s choices?

Many readers have noted the imbalance of power between David and Bathsheba. Because of this power imbalance, by modern standards their sexual encounter is not consensual. It seems the prophet Nathan doesn’t hold Bathsheba responsible, either. In his parable, Bathsheba is portrayed as an innocent lamb. The only person responsible for the situation is the rich man, i.e. King David.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS:

The David and Bathsheba story “interprets sin as having cause and effect.” (14) While Bathsheba isn’t condemned for David’s actions, she does suffer the consequences of David’s sins. Can you think of a time when your actions had negative consequences for others? How have you noticed the effects of larger societal sins?

Read 1 Kings 11-31.

When King David grew old, there was uncertainty over which of his sons would succeed him as king. Bathsheba’s son Solomon, also called Jedidiah, was not David’s firstborn, but because of his mother’s actions, became king of Israel. Solomon was known for his great wisdom.

In this passage, we see Bathsheba is brave and cunning. There is no other record of David’s oath to Bathsheba in verse 17. Perhaps she’s taking advantage of David’s old age, or perhaps David made a promise that was not chronicled. Either way, we see Nathan go to Bathsheba to make a plan. Bathsheba goes before the king unsummoned, a choice not without risk. She is deferential but astute. “Bathsheba shows she can hold her own–even with the king. She has found her voice and uses it to secure not only her future but the future of Solomon and thus the future of Israel.” (15)

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS:

The prophet Nathan approaches David with a parable in 2 Samuel. In 1 Kings, he seeks out Bathsheba during a turbulent political period. Years have passed, and the text doesn’t say how the alliance between Nathan and Bathsheba developed. Using your sacred imagination, what do you think the relationship between Nathan and Bathsheba was like?

Bathsheba goes from being acted upon to taking action. What in your life has compelled you to take action?

What do you think Jesus learned from Bathsheba’s story? What have you learned?

Closing Prayer: God of Survivors, may the world know your justice. Like Bathsheba, give us strength to survive wrongdoing. Like Nathan, give us courage to speak the truth. And if we, like David, have power, give us wisdom so we may use our power for good.

CONCLUSION

Advent is a time of expectant waiting. In this study, we’ve used the women of the past to look forward to the coming of Christ. We hope you've found these women’s stories helpful, whether in your understanding of Jesus or your own self-understanding. Now that you’re well-acquainted with Jesus’ foremothers, we’ll close with the words of his mother, Mary.

The words of Mary, Mother of God:

“My soul magnifies the Lord,

and my spirit rejoices in God my Savior,

for he has looked with favor on the lowly state of his servant.

Surely from now on all generations will call me blessed,

for the Mighty One has done great things for me,

and holy is his name;

indeed, his mercy is for those who fear him

from generation to generation.

He has shown strength with his arm;

he has scattered the proud in the imagination of their hearts.

He has brought down the powerful from their thrones

and lifted up the lowly;

he has filled the hungry with good things

and sent the rich away empty.

He has come to the aid of his child Israel,

in remembrance of his mercy,

according to the promise he made to our ancestors,

to Abraham and to his descendants forever.”

Luke 1:44-46

REFERENCES:

(1) Introducing the New Testament: Its Literature and Theology, by Joel B. Green, Marianne Thompson, and Paul J. Achtemeier (2001)

(2) Mother Roots: The Female Ancestors of Jesus by Helen Bruch Pearson (2002)

(4) Reading the Women of the Bible by Tikva Frymer-Kensky (2002)

(8) “Rahab: Bible” by Tikva Frymer-Kensky, updated by Carol Meyers

(11) “Bathsheba and Preaching in the #MeToo Era” by Sara M. Koenig

(12) Womanist Midrash: A Reintroduction to the Women of the Torah and the Throne by Wilda C. Gafney (2017)